Bi-te Size Bits are short(ish) explainers on film theory or history, written in a (hopefully) fun and accessible way so that you can take the film bro in your life down a peg.

It took me a while to realise I was bi because the kind of bi I am is not talked about or depicted much (or sometimes claimed to not even ‘count’). While the relatively mundane twists and turns of that journey are a tale for another day1, as a bi gal on the ace spectrum2 I’ve always been very keenly aware of when attempts to combat bi erasure can sometimes double down on other forms of exclusion that narrow our perception of what being bi is and who can call themselves that.

Bi erasure can’t be solved by just one approach. There are many other biases that come into play when we make or consume art that we need to be conscious of. It doesn’t mean that every single depiction needs to tick every single representational box, but we should make sure that on the whole we are trying to paint a more diverse picture. Let’s examine some of the pitfalls of combatting bi erasure and what we can do to course correct.

Need some background on bi erasure? Take a look at Part 1 for an introduction

You don’t have to kiss to count

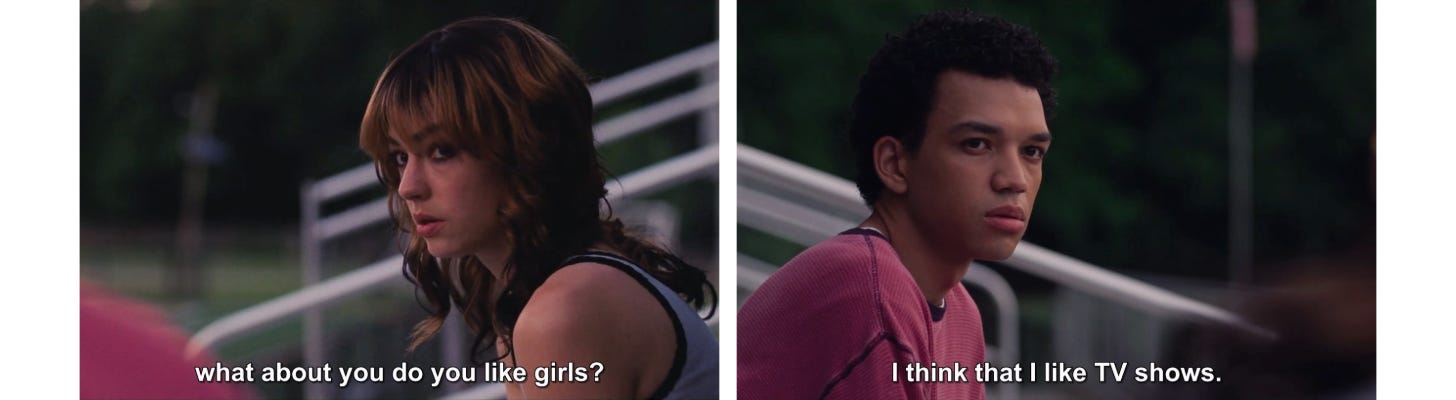

While being bi describes who you are attracted to, that attraction (in real life and in film) does not need to be validated by hooking up with someone. You're still bi even if you’ve never been romantically or sexually involved with someone of another gender, or same gender, or no one at all. There isn’t some kind of punch card you need to fill before you get a bi badge.

When people discuss bi or other queer ‘scenes’ in movies, they are often referring to the scenes where people kiss or have sex. But we should be careful not to judge the whole of queer representation on these single scenes or necessitate these kinds of scenes to count for representation. If a character is bi and in a scene, that scene is still bi representation no matter what they are doing in it.

This is important to not only ensure that characters are not just reduced to their sexuality but can also be a part of validating experiences of being bi that aren’t centred around sex and relationships. This applies to people who are ace3, aro4, or those who (for a range of reasons) just don’t centre those experiences that much in their lives.

This is part of combatting compulsory sexuality, defined by ace scholar Angela Chen as

“a set of assumptions and behaviours that support the idea that every normal person is sexual, that not wanting (socially approved) sex is unnatural and wrong, and that people who don’t care about sexuality are missing out on an utterly necessary experience”.5

There is a similar ‘compulsory’ nature to romantic relationships and the ways these ‘should’ be carried out (like getting married). And when we say a film is not bi enough because it doesn’t have enough sex or kissing or romance, we are feeding into that overarching narrative that says someone in the real world isn’t bi enough if they don’t have a certain amount of sex, kisses, romances, etc.

Of course, there is a fine balance to strike with this. There can be genuine reasons to lament the lack of sex or relationships between queer characters in film, as for a long time they were intentionally not shown or depicted very chastely to avoid censorship or upsetting straight audiences6. We don’t want to slide back into that, and we should support good representations of bi intimacy when we see it.

It can be hard to know how to conduct this balancing act. One tip is to take into consideration the wider genre or tone of the film and how it fits in with other films in the genre. For example, while the depictions of queer characters Loki and Valkyrie in the Marvel franchise are quite chaste, so is the Marvel franchise as a whole when it comes to relationships. In this case, you could argue they aren’t really treating those characters all that differently in terms of depictions of sex. However, if you put this same representation in a franchise that was generally much more sexually explicit, like The Boys (2019-present), then it would flag more concerns about disparity in bi representation.

Give space for friendships

Connected with those previously covered points about combatting compulsory sexuality and romanticism, try not to assume that a romantic or sexual relationship is the relationship pinnacle. While queering is a fun and important part of creating a space for ourselves in art, make sure you are also giving space for the importance of depictions of friendship, which are just as valuable in life.

This is an area that gender bias often comes into play. We are much more used to films about female friendships, and while they are not immune from queer readings, female friend films like Clueless (Amy Heckerling, 1995) or Bridesmaids (Paul Feig, 2011) are much less likely to be interpreted as gay than films that centre male friendship like The Lord of the Rings (Peter Jackson, 2001) or Top Gun (Tony Scott, 1986). Partially because of the bias we have around platonic male intimacy, there are very few films that centre on male friendships, particularly vulnerable and open ones that show men sharing their feelings or physical connection (like hugging). I am not saying we should never indulge in the queer interpretations of these movies (I’ve mentioned the strong gay vibes of Top Gun and The Lord of the Rings in this substack before) or that queer interpretations can’t exist alongside the platonic, but we do need to be aware of how our bias in how we see movies can seep into how we see real people.

In this toxic masculinity hellscape we live in, normalising and celebrating close friendships is needed (though it is not lost on me that there is also a lot of homophobia to address in the hetero male world that leads to adverse reactions to close male friendship7). It’s also, again, a way to validate the experiences of some ace or aro people. By equalising the importance of friendship with other forms of intimacy we can feel more fulfilled in various kinds of relationships, and are therefore less likely to settle for marrying an absolute twat just because we are told romantic, sexual partnership is the supposed be-all and end-all.

Please continue to bring your gay reading goggles to those friendship films, but it’s worth asking yourself some questions around why you are choosing that reading or where you might be applying that reading to some groups more than others. Ask yourself some of the following, and if the answer to any of them is ‘yes’, maybe work on that a bit8:

Do I think friendships are a lesser form of relationship?

Do I read some gender dynamics as queer more often than others?

Do I apply these assumptions in real life and not just to movies?

Do I have strong friendships in my life? How do I value these amongst other relationships?

And related to that: do I make judgements about people in my life who aren’t in romantic relationships? Do I assume they are less happy or less emotionally fulfilled? Have I said or done things that could be making them feel this way?

The best male friendship film of all time? Miami Connection (Y. K. Kim, Park Woo Sang, 1987) celebrates pals, taekwondo, and being in a band that fights drug dealers. The song above depicts the moving performance of ‘Friends’ by the film’s band Dragon Sound.

It’s not who you end up with

To finish up, here is a short tip. Don’t judge the quality of bi representation just on who the character ends up with. A character can still be bi even if they end up with a partner of the opposite gender. This is not a failure of representation or a lesser form of bi representation. As with the other two points in this piece, there are, of course, complexities to this, and the film itself could be trying to drive a narrative that draws you to certain biphobic conclusions. But you don’t need to add that subtext if it isn’t there. In real life, someone isn’t more or less bi based on who they are with, and we don’t need to judge films with that criteria either.

Further reading

Want more than a bi-te size bit of knowledge? Some recommended learning:

A book: Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex by Angela Chen is a must read. Compulsory sexuality impacts us all, and it’s worth reading whether or not you are ace.

A movie: for a movie that explores the social stigma around close male friendships, check out the completely emotionally devastating film Close (Lukas Dhont, 2022).

Let’s do this together

I would love to get your comments and insights on my work so we can grow this place together. Please like and share and comment and all that other stuff. It’s much appreciated.

It involves a coke advert and Janelle Monáe

The ‘ace spectrum’ describes various experiences of low, infrequent, conditional or no feelings of sexual attraction to other people. Terms within this umbrella include asexual (no sexual attraction), demisexual (sexual attraction only to someone you are romantically attracted to) and grey sexual (infrequent sexual attraction). I have never totally felt aligned with any one term, though the one I use the most often when asked is demisexual.

See previous footnote for the definition

Aro is an umbrella term used by people who don’t typically experience romantic attraction. Check out the Stonewall ‘5 things you should know about aromantic people’ for a good intro.

Chen, Angela. Ace: What Asexuality Reveals about Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex. Beacon Press, 2020.

San Filippo, Maria. The B Word: Bisexuality in Contemporary Film and Television. Indiana University Press, 2013.

Let us not forget the ‘buffer seat’ phenomenon of some men feeling it’s too gay to sit next to your bro at a cinema

This isn’t a strict call to police your every thought. It’s hard to undo the bias we are brought up with. Don’t beat yourself up, just keep trying.

Lovely stuff, as usual. Hope your holiday was everything you wanted it to be and more!!