When exploring queer film history it is almost impossible to over look Morocco (1930)- a classic of the pre-code Hollywood era, brimming with influences from Weimar Germany and inseparable from the real life glitz and glamor of it’s star Marlene Dietrich. Featuring one of the few kisses between two women in a film for this period in Hollywood, the movie, this scene, and it’s star have become iconic, often obscuring a more complex reality. Let’s see what we can tease out of this grand mythology.

This essay contains discussion of LGBTQIA+-phobia, including direct quotes. There are some quotes that describe LGBTQIA+ people in a way that is now outdated.

This is a spoiler-free essay.

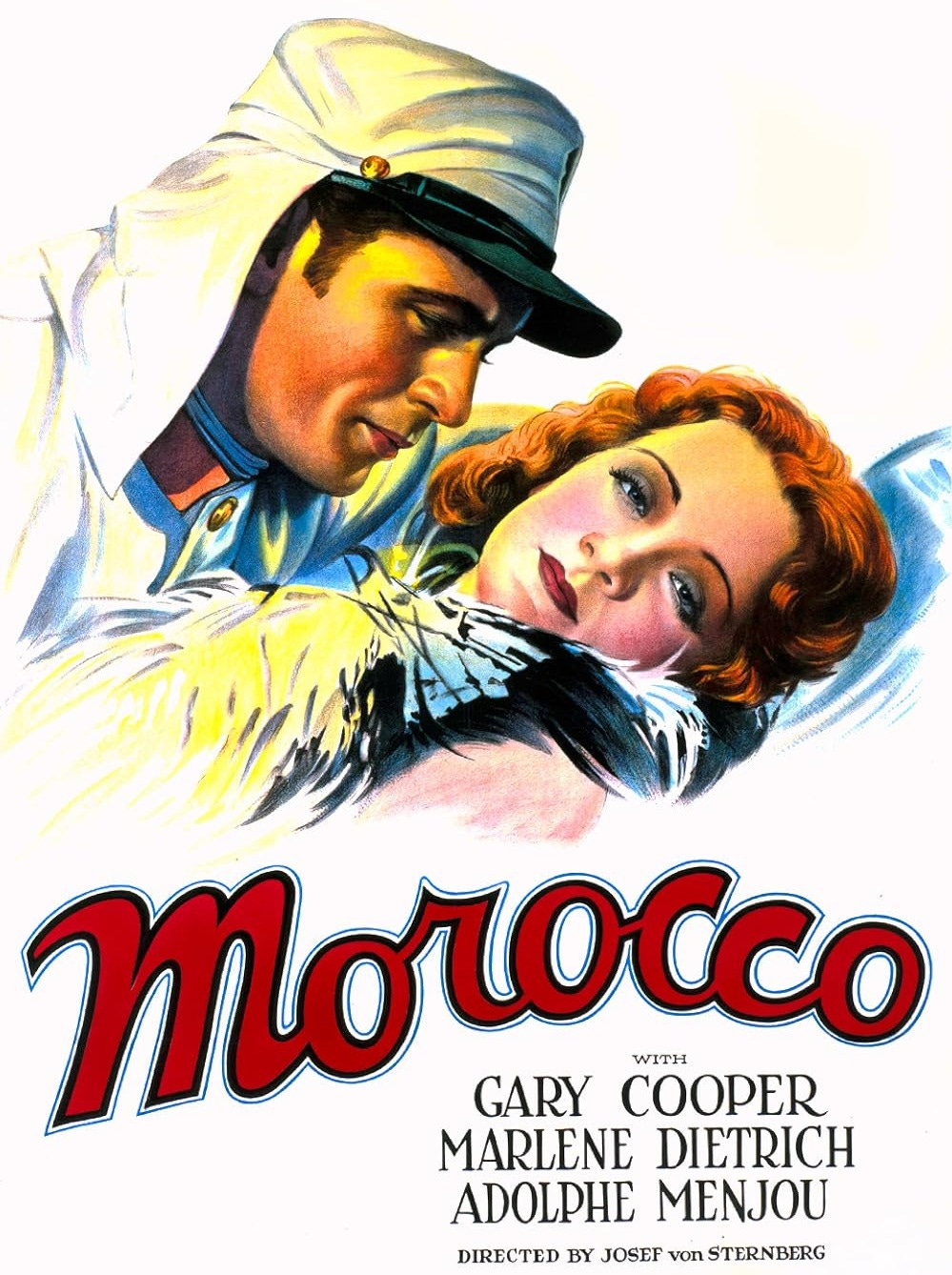

Film Details

Director: Josef von Sternberg

Writer: Jules Furthman (based on a play by Benno Vigny)

Stars: Marlene Dietrich, Gary Cooper, Adolphe Menjou

Genres: Drama, Romance

Theatrical Release Date: Nov. 1930 (USA)

Country and Language: USA, English

Running time: 1hr 32min

Setting the scene

It’s 1930 and something big is about to emerge from Germany. It’s been a year since the Wall Street Crash triggered the Great Depression, which feels like a kick in the teeth after everyone had only just recovered from the Great War that ended in 19181. And it’s not just the common man that is suffering, those poor, multi-million dollar Hollywood studios are struggling with the dramatic transition to talking pictures that revolutionised cinema just three years ago. Most silent movie stars aren’t as bankable in this new era, and the hunt is on for new talent that looks good and sounds even better.

It’s amidst this atmosphere that Paramount Studios turn their eyes to Berlin, where a rising star and her Austrian leader are making waves.

Enter Marlene Dietrich and Josef von Sternberg (obviously I wasn’t going to say Hitler. Nazism still had a few more years to cook before it got as big as Dietrich).

“Shakespeare wrote that men had died and worms had eaten them- but not for love. Maybe so, but Mr. Shakespeare wrote that without having seen Marlene Dietrich in Morocco.”

Morocco tells the story of a jaded cabaret performer (Dietrich) who, against her wiser judgement, falls for a womanising legionnaire (Gary Cooper). Amidst the sand and sweat of Morocco, the two wrestle with their romantic tension while the classic issues of money, duty, and honour interfere here and there.

Also, in the first twenty minutes of the film, Dietrich dons a tuxedo, eyes up a woman in the audience, and kisses her.

The history of Morocco is difficult to disentangle from the history of Marlene Dietrich. Both have become instrumental facets of queer cinema history, with these individual iconographies feeding off each other to create something mythical. Dietrich is often remembered as a fearless, openly bisexual woman who dazzled on the screen and courageously contributed to the war effort against the Nazis. Morocco was her first English-language role, which brought her to the USA just before the Hays Code2 came into force and watered down any attempt to depict life on screen with anything other than a puritanical outlook.

In Morocco and Dietrich we have created icons and there are plenty of retrospectives that will celebrate that. I am more interested in looking behind the haze of the legend. There is a lot of mess you have to ignore or simplify to make something a narrative, and, again, you can read that very satisfying narrative elsewhere. This essay is going to be a place for the mess.

Messing with Morocco

It’s tempting to view this kiss as the only bi moment in the film; however, being bi isn’t something that needs to be validated or maintained by physical intimacy with others. Nor do bi people need to be routinely clocking in time with various genders to qualify for the title. So if you agree Dietrich’s character is bi based on her behaviour in this scene, the bi representation continues on in the film just by her existing in it.

Not all critics have characterised the kiss this way. In Vito Russo’s landmark film theory book The Celluloid Closet, he glosses over the impact of Morocco, stating:

“Dietrich’s intentions are clearly heterosexual; the brief hint of lesbianism she exhibits serves only to make her more exotic, to whet Gary Cooper’s appetite for her and to further challenge his maleness”.

Or, as Katey Rich wrote in Vanity Fair in 2023:

“The kiss in Morocco is more of a provocation than an expression of lust, the ’30s equivalent of Katy Perry’s ‘I Kissed a Girl.’”

These are valid modern takes on the scene. A post Madonna-Britney VMAs kiss world is one divided on the necessity of seemingly performative smooches. But the kiss in Morocco wasn’t rolling off the back of a banging Britney rendition of Like a Virgin. It was made by European filmmakers entering the world of Hollywood in the 1930s. That context is very important.

Director Josef von Sternberg wrote that both the kiss and Dietrich’s outfits in the film were intentional reflections of a more mature vision of sexuality:

“The formal male finery fitted her with much charm, and I not only wished to touch lightly on a Lesbian accent but also to demonstrate that her sensual appeal was not entirely due to the classic formation of her legs.”3

These outfits were not performative. They reflected things Dietrich had often worn in Berlin. The kiss was also something von Sternberg and Dietrich viewed as innocuous but recognised this was likely to be more scandalous in the US4. It can be easy to forget this liberal part of German history amidst what we know followed, but from the 1920s up until the early 1930s, Germany, and particularly Berlin, were the definition of liberation under the Weimar Republic. Not in a concrete political way (women and queer people still didn’t have actual rights), but there was a social acceptance of less rigid, less patriarchal lifestyles that was blossoming in this era. As observed by Sternberg:

“To differentiate between the sexes was, to make an understatement, confusing. Not only did men masquerade as females, wearing false eyelashes, beauty spots, rouge and veil, but the woods were full of females who looked and functioned like men. A third species, defying definition, circulated to lend itself to whatever the occasion offered. To raise an eyebrow at all this branded one as a tourist.”5

As mentioned previously, Morocco benefitted from being a ‘pre-code’ film, meaning it was released before the restrictive Hays Code was introduced to tightly police the ‘morality’ of Hollywood filmmaking6. This lack of regulation made it possible for von Sternberg to include these elements and normalise them in the context of the film. The kiss is enjoyed by the rowdy patrons of the cabaret club and is an aphrodisiac rather than a hindrance to Gary Cooper’s attraction towards Dietrich. This is somewhat facilitated by the setting, depicted almost as a fantasy land in the heat of Morocco, where it appears the American visitors engage in debauchery as a norm. The kiss would likely have had less verisimilitude if the movie was set in an all-American country town. But this more escapist setting helps ground the kiss as a regular part of the film’s reality, accepted not only by the characters but also by those who saw the film.

Dietrich’s attire or dalliances seemed to pose no problem to Morocco’s promotion and success. Paramount billed the film as a sweeping romance, and critics were captivated by Dietrich, with no mention or warning about the kiss to be found in mainstream reviews.

Of course, we can’t give too much credit to Hollywood here. If the film pursued the idea of Dietrich’s bisexual interests in more depth, or framed her as torn between Gary Cooper and a woman rather than between him and another man (Adolphe Menjou), I am sure the film reels would have been set on fire and the ashes buried at sea. But there was at least some form of acceptance here, with Dietrich’s iconic Morocco image even being printed in a Silver Screen article on the suits of Hollywood stars:

Dietrich would soon show that this costume choice was not something contained to the film. She became well known for wearing ‘men’s’ clothing, often opting for trousers over skirts or dresses, reportedly spurring a movement of other women following suit (pun intended). It can be tempting to get caught up in mythology here and assume this was an intentional political statement. However, it seems the reason it proliferated so successfully was because Dietrich did it apolitically. Women had dressed this way long before Dietrich, but these were a certain kind of woman. As expressed by Rosalind Shaffer in a 1935 interview with Dietrich about her outfits:

“The most astonishing thing about this one-woman dress reform movement is that it should have originated with a beautiful film star, famous for her femininity and especially for her beautiful legs, which she now conceals with the wide, long trousers of the male mode. If it had been launched by some homely or aging freak, some reformer, some feminist seeking to claim all men’s rights, or some girl-athlete, long on muscle, but short on sex appeal, it would not have been so unexpected”7

Dietrich was a privileged woman, growing up relatively wealthy and in a time of social freedoms in Berlin. She wasn’t wearing what she did to make a point; she was wearing it because she wanted to and had enough social currency to be allowed to do that while evoking curiosity from the press rather than harassment.

“I have always preferred such clothes. In Europe this is not unusual” (Dietrich)8

This doesn’t make what she has done unimportant, but we should remember that many significant moments that catalyse modernity aren’t always done with the intentionality we assume. We should be critical of who society labels as trailblazers for certain cultural movements, because it’s likely there are layers of complexity in why masses choose to follow them rather than the many others who were doing the same thing. With this in mind, it’s time we look a bit closer at Marlene Dietrich.

Messing with Marlene Dietrich

Morocco exploded Marlene Dietrich into a stardom that extended beyond her Paramount contract. Her humanitarian efforts during the war were covered extensively, and she has been lauded as a fierce, independent, bisexual icon. But in making someone an icon, we curate narratives of their life that tell us more about what we want people like her to be rather than what any person actually is. A lot of research I read for this essay celebrated Dietrich, her bisexuality, and her independence. A lot of research I read highlighted her late-in-life reclusiveness, her domineering temperament, and her discriminatory views. It was not often that these two kinds of research crossed over with each other. The mess behind the narrative of Dietrich has left the reality of her fragmented. No one account seemed wholly real.

These are some of the Marlenes I met in my research9:

The star

While she had featured in some silent films previously, her major debut was in The Blue Angel (Josef von Sternberg, 1930). Morocco was Dietrich’s first English-language film after she was contracted by Paramount. Paramount invested heavily in the promotion of Morocco. Copy for the film’s press would laud the beauty and charm of Dietrich, proclaiming “the talking screen has found it’s voice of love”10.

Dietrich would continue to star in Paramount films throughout the 30s, making five more films with von Sternberg. The high expectations set by Morocco were hard to match, but Destry Rides Again (George Marshall, 1939), Witness for the Prosecution (Billy Wilder, 1951) and Judgment at Nuremberg (Stanley Kramer, 1961) kept her name in lights over the decades. From the mid-50s, she would favour singing and cabaret-style performances over filmmaking and pursued this until her retirement in the 1970s.

The war hero

Despite the attempts of the Nazi regime to lure her back to Berlin and the German film industry in the 1930s, Dietrich applied for US citizenship and took part in wartime efforts for the Allied forces. She supported Jewish exiles, donated parts of her film salary to refugees, and performed for Allied troops across the fronts, powering on through performances despite contracting several illnesses. In the documentary Marlene (1984, Maximilian Schell), Dietrich said her motivations were humanitarian rather than political. She could not stand by while innocent people were being brutalised by this regime.

“Too much for me.”

Marlene Dietrich on Hitler in Marlene

The sister

Marlene Dietrich had an older sister who lived in Germany all her life. Records indicate her sister may have run establishments that were frequented by Nazi officials who oversaw the Belsen concentration camp.

The only child

Marlene Dietrich claimed she was an only child.

Wife and mother

Marlene Dietrich married Rudolf Sieber in 1923. They would remain married until his death in 1976. Together they had one child, Maria Riva, who Dietrich missed dearly in her early days in America before her family eventually moved to be with her. Dietrich had a deep love for her daughter and would often talk about her in interviews. Instead of going to Hollywood parties, she would listen to recordings of her daughter’s voice:

“At night I do not go out to parties. I am very lonely. I sit and play over and over those little records, where my Maria talks to me”.11

Dietrich and Sieber had an open relationship, each taking lovers.

Cruel tyrant

In the biography of Marlene Dietrich written by Maria Riva, Dietrich is described as sexist, racist, and classist. Dietrich took her career and image very seriously. Riva says she felt more like a plaything to her mother rather than an actual child and that all in Dietrich’s orbit were part of her image-cultivating machine.

Riva states that her father had a lover that lived in the family home for some time. Dietrich and Sieber would allegedly force this lover to have numerous abortions and eventually had her committed to a mental health hospital where she died.

Lover

Marlene Dietrich took many lovers, both male and female. Her bisexuality was outed in a 1955 gossip column. Though Dietrich never publicly addressed the rumours, her daughter confirmed her mother’s bisexuality in her biography of Dietrich. She was known for the casual nature of her affairs, and some accounts depict her as more interested in romance than sex.

Her rumoured lovers include Frank Sinatra, Jimmy Stewart, Mercedes De Acosta, John F. Kennedy, Édith Piaf, Gary Cooper, and Ernest Hemingway.

Friend

Marlene Dietrich claimed she never had a sexual affair with Ernest Hemingway, but that he was just a very close friend. Dietrich claimed to value friendship more than sexual or romantic entanglements.

“Friendship is the most important human relationship, of far greater importance than love”12.

Trailblazer

Marlene Dietrich flouted social norms of the time by dressing in suits and could be seen more often in trousers than a skirt or dress. She had a strong control of her career and image, requiring that every photo taken of her be approved before publication.

Indifferent individualist

Marlene Dietrich said, “I never ever took my career seriously”13. She had an indifference to stardom, which is what drew people to her. She has no interest in people romanticising her films or her life, stating that she just learnt the lines and said them. Nothing more.

“I was an actress. I made films. And that’s it”14.

She wore trousers because they were most comfortable and did not appreciate that being read as a political statement:

“I started wearing these clothes for my own satisfaction. I do not believe that they suit every woman.”15

Anti-feminist

In Marlene, Dietrich said women have smaller brains than men and spoke against the feminist, gender-fluid legacy of Morocco:

“Don’t talk to me about women’s lib. I hate it. I don’t know politics...I can’t stand women’s lib because they are not like men. Because if they were like men they would be born like men. They are women so stay women. Be happy with it”.16

Lonely

Marlene Dietrich felt alone in her early days in Hollywood. She did not find parties interesting and longed for the comfort of her family.

“I am afraid and lonely”17.

Dietrich would retire to Paris in the late 1970s after her husband’s death. She lived largely as a recluse at this time. Dietrich refused to be filmed when the Marlene crew was granted interview access. Only audio recordings were taken.

Her daughter recounts that Dietrich barely saw anyone in the later years of her life.

I think it is important to have iconic moments. To have points in cinema like Morocco that demarcate when a lot of people finally took notice of something. But I don’t think it’s all that important for us to have icons. It’s not fair to them, and it’s not fair to us. Marlene Dietrich clearly did some important things for representation, intentional or not, that have been part of a wider queer history. We can appreciate that but should remember the people involved in history are just people. We can’t expect the good someone has done in one moment to be all there is to them. We, unfortunately, can’t expect them to be good in every moment. If we do, we will be disappointed or get into sticky corners where we don’t know what to do with the mess that doesn’t fit the narrative.

“There are not only two sides to every story but close to a thousand, and the chances are that not one of them is completely trustworthy. One side of the story that concerns my relationship with Frau Dietrich has long ago been told with the camera in seven films, and it would not surprise me if it were the least trustworthy of all.”

Final Thoughts

Morocco is an interesting product of an interesting time, caught between a waning era of liberation and an oncoming era of oppression. Because that time is the 1930s, the depiction of Morocco itself isn’t the most culturally sensitive at points, which might understandably put some off giving it a go. If you’re just in it for the kiss scene (and fair play to you), that’s an easy YouTube search away. But if you’re interested in this era of films and aren’t put off by the lingering pace and static cinematography of the classic Hollywood era, this is a good one to tick off the list.

Marlene Dietrich is a complicated figure to watch on screen knowing the wider context. She clearly had a frustration with ideology, not wanting to engage with her actions as part of a wider political or social movement. It’s is a privileged thing to be able to exist with that indifference. However, to me, the value of Morocco isn’t that it was transgressive, but that to those making it, it was completely normal. Part of LGBTQIA+ erasure is trying to convince us that the way we exist is new. But the hate for us is far more recent than the reality of us. There have been eras and civilisations of diverse sexualities, genders, and lifestyles as a norm. Binary gender and compulsory heterosexuality are recent traditions. Researching Morocco and seeing this delicate time period it existed in reminded me that there have been societies and cultures throughout time that accepted and normalised queerness. Sometimes so much that it didn’t even need a label. Queerness isn’t progressive. It’s the denial of it by others that is regressive.

And I don’t care if Marlene Dietrich would disagree.

Let’s do this together

I would love to get your comments and insights on my work so we can grow this place together. Please like and share and comment and all that other stuff. It’s much appreciated.

Everyone would get justifiably miffed once again in 1939 when it became clear that the ‘Great War’ of 1914-1918 was just the first instalment.

For a run down of the Hays Code in queer history, see ‘The Hays Code and its lasting impacts’ on the Hankycode substack.

Sternberg, Josef von. Fun in a Chinese Laundry. Columbus Books, 1987.

Mills, Sam. Uneven: Nine Lives That Redefined Bisexuality. 1st ed, Atlantic Books, Limited, 2025.

Sternberg, Josef von. Fun in a Chinese Laundry.

Sternberg, Josef von. Fun in a Chinese Laundry.

The Hays Code had been adopted by studios in the 1930s, but it wasn’t a compulsory requirement until 1934.

Ibid

Sources for this section include the following. Direct quotes are referenced individually:

Dietrich, Marlene. Marlene. Grove Press, 1989.

Ludlam, Helen. “They’re New - Hot! Watch Them!” Screenland, Jan. 1931, pp. 54–55.

“Maria Riva--1993 TV Interview, Marlene Dietrich’s Daughter.”

Meares, Hadley Hall. “Mirror Images: Marlene Dietrich Through Her Daughter’s Eyes.”

Marlene. Directed by Maximilian Schell, Oko-Film, 1984.

Mills, Sam. Uneven: Nine Lives That Redefined Bisexuality

Rogers St Johns, Adela. “Mother.” The New Movie Magazine, Jan. 1931, pp. 32–33

Marlene Dietrich quoted in Rogers St Johns, Adela. “Mother.”

Dietrich, Marlene. Marlene

Marlene. Directed by Maximilian Schell

Ibid

Marlene Dietrich quoted in Shaffer, Rosalind. “Marlene Dietrich Tells Why She Wears Men’s Clothes.”

Marlene. Directed by Maximilian Schell

Marlene Dietrich quoted in Rogers St Johns, Adela. “Mother.”